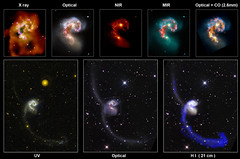

A week ago, on January 21st, the English astrophysicist Steve Fossey gave a telescope workshop for a group of undergraduate students (Ben Cooke, Tom Wright, Matthew Wilde and Guy Pollack) belonging to the University College of London (UCL). As usually happens in the British capital, the sky was practically covered by clouds. However, Fossey and his students used the automatic 35 cm telescope of the University of London Observatory to spot the famous starburst galaxy M 82. Located at 12 million light-years away in the constellation of Ursa Major (The Big Dipper), the galaxy M 82 hosts an intense star-formation burst, being its light dominated by young, hot, massive, blue stars. As consequence of this frenetic activity, M 82 possesses long jets of hot gas that has been expelled from the center of the galaxy. Therefore, it is not casual that the students chose this galaxy as a target for their assignment. While Fossey was centering the galaxy in the field of the telescope he realized that there was a bright star which should not be there. They checked that this new star was real using another telescope of the Observatory. As clouds were approaching, they quickly took some few images in different filters. The first analysis was doubtless: they had just discovered a supernova in the galaxy M 82.

Discovery image of type Ia SN2014J in the starburst galaxy M82 (below) compared with an older image of the galaxy before the supernova exploded (top). The discovery image was obtained at 19:20 UT, 21st January 2014 using the automatic 35 cm telescope of the University of London Observatory. Credit: UCL/University of London Observatory/Steve Fossey/Ben Cooke/Guy Pollack/Matthew Wilde/Thomas Wright.

In just one day, amateur astronomers and professional astrophysicists used their telescopes to study M 82. These observations soon confirmed the discovery made by Fossey and his students. Actually, some astronomers even found that they had taken data of the galaxy and the supernova a week before the official discovery, but the new exploding stars was unnoticed by them. A couple of days after the discovery, a group of astrophysicists led by Yi Cao (Caltech) got the first optical spectrum of the supernova using the 3.5m ARC Telescope at Apache Point Observatory (New Mexico, USA). The analysis of this spectrum showed that the progenitor of the supernova was a white dwarf, and hence the explosion was classified as a type Ia supernova. The official name of this exploding star is SN 2014J. It has not reached its maximum brightness yet: when Fossey and his students discovered the supernova, it was 2 weeks before when we expect this happens. Right now it is so bright (around 10th magnitude) it is very easy to spot using a small amateur telescope. Perhaps even it can be seen using binoculars when the supernova reaches its maximum brightness in a week or so!

Hence, it is not difficult to understand that SN 2014J and M 82 have been the main astronomical news in the last week. Using the 4.2m William Herschel Telescope (WHT), which is part of the Isaac Newton Group, located at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory in the beautiful island of La Palma (Canary Islands, Spain), the astrophysicists Manuel Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain) and Lluís Galbany (DAS/UC, Chile) have observed with great detail both the supernova and the galaxy. Between Thursday 23rd and Sunday 26th January they used the ISIS spectrograph, as well as the ACAM instrument (Auxiliary-Port Camera), of the WHT to get images and spectra of the supernova. I was continuously in touch with them as I’m part of their research team (actually, I’m co-supervising the PhD thesis which is conducted by Manu). I originally planned to travel to La Palma to be helping on these observations, however this was colliding with my support activities at the Anglo-Australian Telescope (Siding Spring Observatory, NSW, Australia). Manu and Lluís sent me the data as they were coming from the WHT, and I was reducing, combining, and getting the preliminary images and spectra of this object!

The image below shows the supernova SN 2014J and the galaxy M 82 using the data obtained with ACAM. I tried to get all the important details of this puzzling object: the dust lanes crossing the disc (dark-yellow), the strong star-formating bursts (blue) and even the filamentary structure of the super-galactic wind that M 82 possesses (in red). This feature is hot, ionized gas which has been expelled from the center of the galaxy and here it is seems perpendicular to the galactic disc. SN 2014J very brightly shines at the west (right) of M 82 galactic center.

Colour image of starburst galaxy M 82 with the type Ia supernova SN 2014J. M 82 lies at 12 million light years from us, in the Ursa Major constellation. The supernova is marked with two white lines. The data needed to get this image were taken using the ACAM instrument located at the Cassegrain focus of the 4.2m William Herschel Telescope (WHT) (Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain). We got data in u, g, i, r, and Hα filters. Data coming from the u filter (2 x 200 seconds exposures) are colour-coded in blue; data in the g filter (3 x 100 seconds exposures) are colour-coded in cyan; data in the i filter (3 x 100 seconds exposures) are colour-coded in green; data in r filter (3 x 300 seconds exposures) are colour-coded in red. The majority of the data were obtained last 24th January, at 04:40 UT. Data in r and u filter were taken on 25th January, at around 06:00 UT. The Hα data (4 x 300 seconds exposures), which are colour-coded in red, were taken on 26th January at 06:30 UT. Data coming from the Hα filter clearly reveals the super-galactic wind of M 82. All data were reduced and combined using standard IRAF routines. The colour composition was obtained using Photoshop. The field of view is 8 arcminutes and the resolution 0.25 arcsec/pixels. However, the seeing was not too good, between 2 and 5 arcsec.

Credit: Observers: Manuel E. Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain) & Lluís Galbany (DAS / UC, Chile). Data processing and color image composition: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO / MQ, Australia). Support astronomer: Chris Benn (ING, UK), Telescope Operator: José Norberto González (ING, UK). Research Team: Manuel E. Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain), Mercedes Mollá (CIEMAT, Spain), Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO / MQ, Australia), Lluís Galbany (DAS / UC, Chile),Aurelio Carnero (ON, Brazil), Inma Domínguez (UGR, Spain), & Pepe Vílchez (CSIC / IAA, Spain).

In addition, we have already analyzed the low-resolution spectrum of the SN 2014J obtained using ACAM. This spectrum gets all the optical range, between 3500 and 9500 Angstroms, and clearly identifies the object as a type Ia supernova. The main features are absorption bands of iron (Fe II and Fe III), magnesium (Mg II) and silicon (Si II) between 4000 and 5000 A. These bands actually are blends of absorptions due to these metallic elements. Indeed, astrophysicists expect the intensity of these bands will be changing as the supernova evolves, as the chemical abundances and ionization of each species vary as some elements are converted into others and more material coming from the center of the dead star is observed. Even so, it is a surprise to find these absorption bands almost 10 days before the supernova reaches its maximum brightness. The spectrum also shows absorptions of sulfur (S II) at 5240 and 5450 A, a strong absorption by silicon (Si II) at 6150 A, and absorptions of calcium (Ca II), sodium (Na I) and oxygen (O I). Some features are actually created in the Earth atmosphere and hence they do not belong to the supernova, these are labelled as “Tel” (from “Teluric lines”). However, the feature which interested us most was the carbon absorption (C II) at 6580. This line indicates that the progenitor of the supernova was a white dwarf composed by carbon and oxygen (as it happens in the majority of the white dwarf). However, it is uncommon to observe this line in type Ia spectra. This suggests that the surface of the white dwarf has not been completely burnt during the explosion. All absorption lines are found “blue-shifted”, that is, at shorter wavelengths that those expected. That is a consequence of the high speed at which the material is moving, expanding fast away from the dead star. The measurement of the C II and S II lines observed in our ACAM optical spectrum indicates that this material is moving at around 15 000 km/s!

Low-resolution optical spectrum of the type Ia supernova SN 2014J discovered in the galaxy M 82 obtained using the ACAM instrument at the Cassegrain focus of the 4.2m William Herschel Telescope (WHT) (Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain). The intensity or relative flux (“Arbitrary Flux”, vertical axis) is plotted versus wavelength (“colour”, horizontal axis). The main features, which includes absorption lines of iron, magnesium, silicon, sodium, calcium, oxygen and carbon, are labelled. The spectrum combines two expositions of 200 seconds each using the ACAM V400 grism. The data were obtained last 25th January at 7:10 UT, which approximately corresponds to Epoch -11 days. It is expected the supernova reaches its maximum brightness in that time. The reduction of the data and the wavelength calibration was performed using standard IRAF routines.

Credit: Observers: Manuel E. Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain) & Lluís Galbany (DAS / UC, Chile). Data processing and color image composition: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO / MQ, Australia). Support astronomer: Chris Benn (ING, UK), Telescope Operator: José Norberto González (ING, UK). Research Team: Manuel E. Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain), Mercedes Mollá (CIEMAT, Spain), Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO / MQ, Australia), Lluís Galbany (DAS / UC, Chile),Aurelio Carnero (ON, Brazil), Inma Domínguez (UGR, Spain), & Pepe Vílchez (CSIC / IAA, Spain).

Interestingly, the project that Manuel Moreno-Raya (CIEMAT, Spain) and his research team, composed by Mercedes Mollá (CIEMAT, Spain), Lluís Galbany (DAS / UC, Chile), Aurelio Carnero (ON, Brazil), Inma Domínguez (UGR, Spain), Pepe Vílchez (CSIC / IAA, Spain) and myself, was observing at the WHT was focused in obtaining deep, high-quality data of galaxies hosting type-Ia supernova. The idea is to quantify the physical and chemical properties of these host galaxies with the final aim of getting a better understanding of the parameters which control the brightness of these supernovae and apply these new measurements to improve the accuracy to very distant galaxies. This research is the main part of the PhD thesis project that Manu is conducting. Besides the observations of M 82 and the SN 2014J, we also got deep intermediate-resolution optical spectroscopy data of around 20 galaxies. These data still have to be analyzed in detail, something that will take months.

SN 2014J is the type-Ia supernova closest to the Earth since that Johannes Kepler observed in 1604. The Kepler’s Supernova actually exploded in our Galaxy, at just 20 thousands light-years from us, and it was so bright it was seen with the naked eye, being the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and the Moon. The type Ia supernova SN 1972e was also very close to us, as it exploded in the dwarf galaxy NGC 5253 (*). NGC 5253, which lies at a distance of 13 million light years, is in some way a similar object to M 82, as it also hosts a very powerful star-formation event. SN 1972e became the prototype object for the development of theoretical understanding of Type Ia supernovae, but this position may change with all the data that are coming from SN 2014J. What surprises will provide this new supernova? Can the new data be used to get a better understanding of the type Ia supernovae as a cosmological distance estimators and help to discover the nature of the mysterious dark energy which induces the expansion of the Universe? This research has just started.

UPDATE: Part of the information included in this post was used to prepare a telegram for ATel, The Astronomer’s Telegram, number 5827, Broad and narrow band imaging and spectroscopic follow up of SN2014J in M82, published on 28 Jan 2014; 18:30 UT.

(*) I should tell you many more things about the dwarf galaxy NGC 5253… It was my nightmare for some few years and after performing a very complete and detailed multi-wavelength analysis of this weird object I’m still not sure what is happening in there!