Story based on the news release about Kathryn’s Wheel I prepared for the Australian Astronomical Observatory webpage.

The majority of the galaxies in the Universe can be classified into two well-distinguished classes: spiral galaxies (as our own Milky Way Galaxy) or elliptical galaxies. Spiral galaxies have on-going star-formation activity, possess a lot of young, blue stars, and are rich in gas and dust. However elliptical galaxies are just made up of old stars, with no signs of star formation, gas and dust. Besides these two large galaxy classes, some galaxies are found to have irregular or disturbed morphologies. That is certainly the case of many dwarf galaxies. A disturbed morphology is typically indicating a galaxy that has experienced an interaction with a nearby companion object. Indeed, all galaxies are experiencing interactions and mergers with other galaxies during their life time: the theory currently accepted about how galaxies grow and evolve naturally explains the building of spiral galaxies as mergers of dwarf galaxies, and the birth of an elliptical galaxy after the merger of two spiral galaxies. This will actually be the final destiny of our Milky Way, when it is colliding and merging with the Andromeda galaxy in around 4.5 billions years from now.

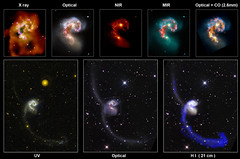

When galaxies collide, stars and gas are pulled out from them by gravity, and long tails of material stripped from the parent galaxies are formed. Famous galaxies in interaction developing these long “tidal tails” are the Mice Galaxies (NGC 4676) and the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038/4039). Very rarely, the geometry of the galaxy encounter is such that a small galaxy passes through the centre of a spiral galaxy creating a collisional ring galaxy. The ring structure is created by a powerful shock wave that sweeps up gas and dust, triggering the formation of new stars as the shock wave moves outwards. The most famous ring galaxy is the Cartwheel (ESO 350-40) galaxy, which is located at 500 million light-years away in the Southern constellation of the Sculptor. However complete ring galaxies are extremely rare in the Universe, only 20 of these objects are known.

Images of the interacting galaxies The Mice (NGC 4676), the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038/4039), and the Cartwheel (ESO 350-40) galaxy. Credit: The Mice: NASA, H. Ford (JHU), G. Illingworth (UCSC/LO), M.Clampin (STScI), G. Hartig (STScI), the ACS Science Team, and ESA, Antennae Galaxies: Robert Gendler, The Cartwheel: ESA/Hubble & NASA.

An international team of astronomers led by

Prof. Quentin Parker (The University of Hong Kong / Australian Astronomical Observatory) has discovered a nearby ring galaxy which in some ways is similar to the Cartwheel galaxy but 40 times closer. The system was discovered as part of the observations of the AAO/UK Schmidt Telescope (UKST) Survey for Galactic H-alpha emission. Completed in late 2003, this survey used the 1.2m UKST at Siding Spring Observatory (NSW, Australia) to get wide-field photographic data of the Southern Galactic Plane and the Magellanic Clouds using a H-alpha filter. This special filter is able to trace the gaseous hydrogen (and not the stellar emission) within galaxies, allowing astronomers to detect the ionized gas from nebulae. The survey films were scanned by the SuperCosmos measuring machine at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh (UK), to provide the online digital atlas “SuperCOSMOS H-alpha Survey” (SHS). When using this survey to search for new, undiscovered planetary nebulae (dying stars which often show ring morphologies in nebular emission) in the Milky Way, the team realised that a very peculiar of these structures was actually found around a nearby galaxy, ESO 179-13, located in the Ara (the Altar) constellation. The reason why this magnificent collisional ring structure has been unknown by astronomers is that it is located behind a dense star field (this area of the sky is very close to the Galactic plane, where the majority of the Milky Way stars are located) and very close to a bright foreground star.

Discovery images of the “Kathryn’s Wheel” using the data obtained at the 1.2m UKST by the “SuperCOSMOS H-alpha Survey” (SHS). The left panel (SR) shows the red image tracing mainly the stars. The three main components of the system are labelled. The central panel shows the image using the H-alpha filter (Hα), which sees both the diffuse ionized gas and the stars. The right panel (Hα-SR) shows the continuum-substracted image of the system, revealing for the very first time the intense collisional star-forming ring. Image credit: Quentin Parker / the research team.

The discovery SHS images of the system reveal 3 main structures (A, B and C) plus tens of H-alpha emitting knots making the ring. Component A is the remnant of the main galaxy, the collisional ring is centered on it. Component A does not possess ionized gas (that is, it does not have star-formation at the moment). On the other hand, component B seems to be the irregular, dwarf galaxy (“the bullet”) that impacted with the main galaxy. Component B does possess a clumpy and intense H-alpha emission.

Astronomers have dubbed this ring galaxy as “Kathryn’s Wheel” in honour of the wife of one of the discoverers, Prof. Albert Zijlstra, (University of Manchester, UK). Kathryn’s Wheel lies at a distance of 30 million light years away, and therefore it is an ideal target for detailed studies aiming to understand how these rare collisional ring galaxies are formed, the physics behind these structures, and their role in galaxy evolution. Interestingly, the collisional ring is not very massive: its mass is only a few thousand million Suns. This is less than ~1% of the Milky Way mass, indicating that ring galaxies can be formed around small galaxies, something that was not considered so far.

(Left) Colour image of the collision, made by combining data obtained at the Cerro-Tololo InterAmerican Observatory (CTIO) 4-metre telescope in Chile. The H-alpha image is shown in red and reveals the star-forming ring around the galaxy ESO 179-13, that has been dubbed “Kathryn’s Wheel”. Image credit: Ivan Bojicic / the research team. (Right) Image showing only the pure H-alpha emission of the system highlighting just the areas of active star formation. For clarity any remaining stellar residuals have been removed. Image credit: Quentin Parker / the research team.

Furthermore, the galaxy possesses a lot of diffuse, neutral hydrogen in its surroundings. This cold gas is the raw fuel that galaxies need to create new stars. Observations using the 64-m Parkes radiotelescope (“The Dish”, Parkes, NSW) as part of the “HI Parkes All-Sky Survey” (HIPASS) revealed that the amount of neutral gas around Kathryn’s Wheel is similar to the amount of mass found in stars in the system. Astronomers are unsure about from where this cold gas is coming from, although they suspect it mainly belonged to the main galaxy before the collision started. However, as the remnant of the galaxy (component A) does not have star-formation at the moment, it seems that the diffuse gas has been expelled from the centre of the system to the outskirts of the galaxy.

The results were published in MNRAS in August 2015.

MNRAS 452, 3759–3775 (2015) doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1432

Kathryn’s Wheel: a spectacular galaxy collision discovered in the Galactic neighbourhood

Authors: Quentin A. Parker, Albert A. Zijlstra, Milorad Stupar, Michelle Cluver, David J. Frew, George Bendo and Ivan Bojicic