This is the English adaptation of the article I published in the Spanish science communication website Naukas.com yesterday, Tuesday 4th June 2019, which was an extended version of the article I wrote for my weekly section “Zoco de Astronomía” in Diario Córdoba last Sunday, 2nd June 2019.

If the light reflected by satellites is not limited, the new “satellite constellations” such as Starlink may not only be a problem for the scientific observations of professional astrophysicists and amateur astronomers but they will also induce a loss for our society, as we could have more satellites than stars visible to the naked eye anywhere in the world during several hours during the night.

For generations and generations we human beings have looked to the heavens and left in them our illusions, hopes, aspirations, goals, even searched for our own origins. The contemplation of a completely starry sky awakens all kinds of feelings in the human being, has defined us as people, as cultures and as societies. Being under a sky full of stars on a moonless night is really one of nature’s greatest spectacles we can enjoy. An unique show that, little by little, we are losing.

First it was the light pollution. As cities grew and technology was able to produce electricity cheaply, we began to shine irresponsibly. It is incredible how little aware we are of the problem of light pollution: billions of euros are lost every year around the world illuminating the sky, something that has as ominous consequences the impact on the environment and human health, in addition to erasing at a stroke until 95% of all the stars we could see in the sky. This generation, the one that is growing now, is the first one in all history that has not been able to enjoy a dark starry sky. Sadly, in many large cities of the civilized world children believe that the true color of the night is orange (or blue, after the introduction of the terrible lighting using LEDs).

These days we are starting to be aware of a new threat to enjoy the starry sky. This thread is global, and not local as the light pollution is. After all one “can escape” from the light pollution, even for a few days, taking refuge in dark places in the middle of the countryside, on the tops of mountains, in the middle of the ocean, on deserted islands or in the middle of the desert. But we could not escape this new threat if it materializes.

On Thursday, May 23, 2019, the US private space company SpaceX , led by the famous Elon Musk , launched a group of 60 satellites in low Earth orbit . This group of satellites is the first of a super satellite complex (also referred to as a “constellation“) known as Starlink . In the next few years, SpaceX has planned many more launches of these individual satellites, perhaps even surpassing 12,000 units in a decade. The goal of Starlink is to get internet service to everyone at a low cost. But these satellites, which have solar panels and metal surfaces, are visible to the naked eye. Since the launch of these 60 Starlink satellites have been seen by hundreds of thousands of people. These sightings have unleashed the controversy: the satellites are much brighter than expected.

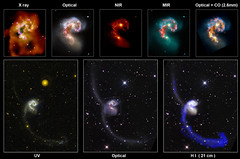

(a) Coverage of the Starlink constellation. (b) Starlink satellites. (c) Starlink satellites prior to being released by the second stage of Falcon 9. (d) Image of the group of galaxies NGC 5353 with the diagonal traces of the Starlink satellite group crossing the field of view, as observed on Saturday 25 of May. Credits: (a) Mark Handley, (b, c) Space X (d) Victoria Girgis, Lowell Observatory.

How bright? It depends on the specific moment, but on some occasions they can equal the brightness of the brightest stars, with flashes that exceed the brightness of Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. There are internet pages and apps that let you know what artificial satellites can be seen from a particular place on a particular night. Searching for the passage of the International Space Station (ISS) is quite common, for example, and usually like everyone. But the problem here is that there would be 12,000 satellites up there: although the space around the Earth is large, it is not so large, and there will always be tens or hundreds of satellites visible at a particular moment of the night. So much that the worst estimations indicate that there might be more satellites moving through the sky than fixed stars that we can see with the naked eye in urban areas.

Some astronomers have tried to make calculations to account for the problem. For example, the Dutch astrophysicist Cees Bassa accounted for only 1,600 satellites (the first phase of the Starlink constellation), estimating that in places with latitudes equal to that of London (52 degrees north) there would always be 84 satellites visible at any time, of which 15 would be easily visible, especially in the summer months when the sun does not fall much over the horizon. The visibility of satellites is worse in the hours close to sunset or sunrise. With 12 thousand satellites he estimated that between 70 and 100 satellites would be visible from any point of the sky for much of the night. Of course, the exact brightness of these satellites once they are in their final orbit is still unknown, but right now it is feared that many of them can be really as bright as the stars that are seen from places with high light pollution.

Graph showing the number of Starlink satellites visible in latitudes of 52º (London). It assumes 7500 satellites at 340 km altitude, with 75 orbital planes, each with 100 satellites. Only satellites that have a height greater than 30º above the horizon are included. The horizontal axis collects the time of day and the vertical axis the day of the year. The green and red stripes show the sunrise and sunset, respectively. The color yellow corresponds to 40 satellites, the color black to 0 satellites. Following this figure there would be an average of 40 satellites illuminated at any time in the hours around twilight, and all night in the months near the summer solstice (June and July). Credit: Cees Bassa.

Amateur astronomers are screaming blue murder. And many professional astrophysicists too. Some have had curious interactions with Elon Musk, who in this case does not seem to be setting a good example because he has helped spread bad information. For example, in a tweet he said that “the ISS looks very bright because they turn on the lights“, something that is completely false because it simply reflects the light of the Sun, just as Starlink’s satellites do.

In addition to the loss of the starry sky to the general public, the large increase in artificial satellites in low Earth orbit is a huge problem no longer to amateur astronomers (they are used to occasionally have “traces” of artificial satellites in their photos, but this is corrected by obtaining many photos and averaging when stacking) but to professional astrophysicists. Astrophysical images are often “deep ” (exposures of many minutes, sometimes an hour) but few (2 – 5 images per target), so the “clean” data would be much more complicated. And to this we have to add that the many calibration images (for example, “flatfields“), that are fundamental for the correct scientific use of the data, would also be affected, and it is necessary to invest more time than is currently used in these shots. calibration to make sure they are valid.

In the coming years new telescopic installations will be inaugurated. Some of them are costing a lot of money and are thought to take images in very large fields of the sky. For example, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) will be capable of mapping the entire sky in only 3 nights. Nonetheless, this early morning LSST has issued a statement notifying that, after a preliminary study, the impact of the satellites of the Starlink constellation would be very small for LSST. That is because the algorithm that combines individual frames (3 of them) into a final scientific image should be able to eliminate the satellite traces.

But it is not only the large telescopes: there are dozens of “modest” professional telescopes (say, between half a meter and 4 meters in size) that perform fundamental scientific work, for example, the hunting of asteroids and comets or the search for supernovas. All these scientific observations would also be affected by satellite traces.

Another problem added: the radio-interference that the satellites would cause in radio telescopes . This is something well known by professionals and difficult to quantify until the satellites are actually there. One of the most ambitious international projects is precisely the SKA ” Square Kilometer Array“, a network with thousands of radio telescopes that will be installed between South Africa and Australia. If constellations of satellites like Starlink are not careful in limiting the frequencies in which they emit and receive they could greatly limit the huge investment in technical and human capital that is being used in SKA. Several professional radio astronomy organizations, including the NRAO ( National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA ), have issued statements insisting that SpaceX has been in contact with them to minimize the impact of radio interference on scientific observation, delimiting “exclusion zones“. These are frequency ranges that should not be used in satellites, to minimize the impact on astrophysical tasks from the ground. But this does not have to be the case in constellations of satellites launched by other companies or other countries.

Here we also have to insist on something else: we do not need to go into space for doing astronomy (as indeed Elon Musk himself suggested): many of these installations (telescopes of class 30 meters and radio interferometers such as the SKA) are only possible on Earth, at least with the current means and budgets. In addition, satellites in low orbit also interfere with the work of space telescopes such as the HST ( Hubble Space Telescope )! It is not common yet, but it is detected in some shots of the HST the passage of artificial satellites as “defocused strokes” .

Trace of satellite in an image of the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: Judy Schmidt.

Early this week, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) issued a statement precisely warning of this problem, notifying that “we still do not understand well the impact of thousands of these satellites visible throughout the night sky and, despite their good intentions, these constellations of satellites can threaten [astronomical observations in optical and radio] “ In the same statement, the IAU asks all the companies involved and legislators to work together with the astronomical community to understand the real impact that satellite constellations may have and thus eliminate or at least mitigate their impact on scientific work and exploration. space.

Indeed, many of us do not expect to suspend these space projects, but we hope that satellite companies take this problem into account, in order to minimize the reflectivity of the satellites and the frequencies in which they operate, and to legislate correctly so that this actually happens. It is no longer just SpaceX: several international companies want to launch their own satellite constellations in the near future, reaching more than 50,000 in just a couple of decades.

In 20 years or so, the children of our world will might see the sky as an orange glow where hundreds of bright spots are continuously moving, losing forever the real beauty of the night sky. And they will not be able to escape from this pollution: it does not matter where you are on Earth, far or near cities, if you’re lost in a desert, in the middle of the ocean or in an astronomical observatory: there could be dozens or hundreds of satellites moving through the sky almost at any moment. Goodbye to the romanticism of Astronomy and identifying the constellations in the sky. Goodbye to a society and young people marveling at the beauty of a dark sky full of stars. They might get the best internet connection, but they will be losing what once it made us dream with the stars.

Links:

- IAU Media Release: https://www.iau.org/news/announcements/detail/ann19035/

- IDA Response: http://www.darksky.org/starlink-response/

- NRAO statement: https://public.nrao.edu/news/nrao-statement-commsats/

- NRAO and GBO statements: https://greenbankobservatory.org/joint-nrao-and-gbo-statement/

- LSST statement: https://www.lsst.org/content/lsst-statement-regarding-increased-deployment-satellite-constellations

- AURA statement: https://www.aura-astronomy.org/news/aura-statement-on-the-starlink-constellation-of-satellites/

- ESO statement: https://www.eso.org/public/announcements/ann19029/

- Royal Astronomical Society statement: https://ras.ac.uk/news-and-press/news/ras-statement-starlink-satellite-constellation

- Articles in media:

- AFP: https://www.afp.com/en/news/826/spacex-satellites-pose-new-headache-astronomers-doc-1h07sd1

- LiveScience: https://www.livescience.com/65586-spacex-astronomers-starlink.html

- Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanocallaghan/2019/05/27/spacexs-starlink-could-change-the-night-sky-forever-and-astronomers-are-not-happy

- The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/01/science/starlink-spacex-astronomers.html

- The Verge: https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/29/18642577/spacex-starlink-satellite-constellation-astronomy-light-pollution

- Science American: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/spacexs-starlink-could-cause-cascades-of-space-junk

- Blog by Daniel Marín (Spanish): https://danielmarin.naukas.com/2019/05/29/las-megaconstelaciones-de-satelites-adios-al-cielo-nocturno-de-nuestros-antepasados/

- Blog Skepchick: https://skepchick.org/2019/06/spacelink-the-sky-and-colonialist-attitudes/

- Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Starlink_(satellite_constellation)

- Threads in Twitter:

- Alex Parker: https://twitter.com/Alex_Parker/status/1132163931378610178

- Daniel Fisher: https://twitter.com/cosmos4u/status/1133542324494057474

- Cees Bassa: https://twitter.com/cgbassa/status/1133827825113423872

and also https://twitter.com/cgbassa/status/1132551806125522945 - John Barentine: https://twitter.com/JohnBarentine/status/1133478040833445889

- Juan Carlos Muñoz: https://twitter.com/astro_jcm/status/1135568400070119424

- Mark McCaughrean: https://twitter.com/markmccaughrean/status/1135525092786671617