How do galaxies grow and evolve? Galaxies are made of gas and stars, which interact in very complex ways: gas form stars, stars die and release chemical elements into the galaxy, some stars and gas can be lost from the galaxy, some gas and stars can be accreted from the intergalactic medium. The current accepted theory is that galaxies build their stellar component using their available gas while they increase their amount of chemical elements in the process. But how do they do this?

That is part of my current astrophysical research: how gas is processed inside galaxies? What is the chemical composition of the gas? How does star-formation happen in galaxies? How galaxies evolve? Today, 21st May 2015, the prestigious journal “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, publishes my most recent scientific paper, that tries to provide some answers to these questions. This study has been performed with my friends and colleagues Tobias Westmeier (ICRAR), Baerbel Koribalski (CSIRO), and César Esteban (IAC, Spain). We present new, unique observations using the 2dF instrument at the 3.9m Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT), in combination with radio data obtained with the Australian Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) radio-interferometer, to study how the gas in processed into stars and how much chemical enrichment has this gas experienced in a nearby galaxy, NGC 1512.

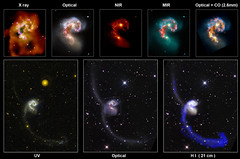

Deep images of the galaxy pair NGC 1512 and NGC 1510 using optical light (left) and ultraviolet light (right).Credit: Optical image: David Malin (AAO) using photographic plates obtained in 1975 using de 1.2m UK Schmidt Telescope (Siding Spring Observatory, Australia). UV image: GALEX satellite (NASA), image combining data in far-ultraviolet (blue) and near-ultraviolet (red) filters.

NGC 1512 and NGC 1510 is an interacting galaxy pair composed by a spiral galaxy (NGC 1512) and a Blue Compact Dwarf Galaxy (NGC 1510) located at 9.5 Mpc (=31 million light years). The system possesses hundreds of star-forming regions in the outer areas, as it was revealed using ultraviolet (UV) data provided by the GALEX satellite (NASA). Indeed, the UV-bright regions in the outskirts of NGC 1512 build an “eXtended UV disc” (XUV-disc), a feature that has been observed around the 15% of the nearby spiral galaxies. However these regions were firstly detected by famous astronomer

David Malin (AAO) in 1975 (that is before I was born!) using photographic plates obtained with the 1.2m UK Schmidt Telescope (AAO), at Siding Spring Observatory (NSW, Australia).

The system has a lot of diffuse gas, as revealed by radio observations in the 21 cm HI line conducted at the Australian Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) as part of the “Local Volume HI Survey” (LVHIS) and presented by Koribalski & López-Sánchez (2009). The gas follows two long spiral structures up to more than 250 000 light years from the centre of NGC 1512. That is ~2.5 times the size of the Milky Way, but NGC 1512 is ~3 times smaller than our Galaxy! One of these structures has been somehow disrupted recently because of the interaction between NGC 1512 and NGC 1510, that it is estimated started around 400 million years ago.

Multiwavelength image of the NGC 1512 and NGC 1510 system combining optical and near-infrared data (light blue, yellow, orange), ultraviolet data from GALEX (dark blue), mid-infrared data from the Spitzer satellite (red) and radio data from the ATCA (green). The blue compact dwarf galaxy NGC 1510 is the bright point-like object located at the bottom right of the spiral galaxy NGC 1512.

Credit: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO/MQ) & Baerbel Koribalski (CSIRO).

Our study presents new, deep spectroscopical observations of 136 genuine UV-bright knots in the NGC 1512/1510 system using the

powerful multi-fibre instrument 2dF and the spectrograph AAOmega, installed at the 3.9m Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT).

2dF/AAOmega is generally used by astronomers to observe simultaneously hundreds of individual stars in the Milky Way or hundreds of galaxies. Without considering observations in the Magellanic Clouds, it is the first time that 2dF/AAOmega is used to trace individual star-forming regions within the same galaxy, in some way forming a huge “Integral-Field Unit” (IFU) to observe all the important parts of the galaxy.

Two examples of the high-quality spectra obtained using the AAT. Top: spectrum of the BCDG NGC 1510. Bottom: spectrum of one of the brightest UV-bright regions in the system. The important emission lines are labelled.

Credit: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO/MQ), Tobias Westmeier (ICRAR), César Esteban (IAC) & Baerbel Koribalski (CSIRO).

The AAT observations confirm that the majority of the UV-bright regions are star-forming regions. Some of the bright knots (those which are usually not coincident with the neutral gas) are actually background galaxies (i.e., objects much further than NGC 1512 and not physically related to it) showing strong star-formation activity. Observations also revealed a knot to be a very blue young star within our Galaxy.

Using the peak of the H-alpha emission, the AAT data allow to trace how the gas is moving in each of the observed UV-rich region (their “kinematics”), and compare with the movement of the diffuse gas as provided using the ATCA data. The two kinematics maps provide basically the same results, except for one region (black circle) that shows a very different behaviour. This object might be an independent, dwarf, low-luminosity galaxy (as seen from the H-alpha emission) that is in process of accretion into NGC 1512.

Map showing the velocity field of the galaxy pair NGC 1512 / NGC 1510 as determined using the H-alpha emission provided by the AAT data. This kinematic map is almost identical to that obtained from the neutras gas (HI) data using the ATCA, except for a particular region (noted by a black circle) that shows very different kinematics when comparing the maps.

Credit: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO/MQ), Tobias Westmeier (ICRAR), César Esteban (IAC) & Baerbel Koribalski (CSIRO).

The H-alpha map shows how the gas is moving following the optical emission lines up to 250 000 light years from the centre of NGC 1512, that is 6.6 times the optical size of the galaxy. No other IFU map has been obtained before with such characteristics.

Using the emission lines detected in the optical spectra, which includes H I, [O II], [O III], [N II], [S II] lines (lines of hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulphur), we are able to trace the chemical composition -the “metallicity”, as in Astronomy all elements which are not hydrogen or helium as defined as “metals”- of the gas within this UV-bright regions. Only hydrogen and helium were created in the Big Bang. All the other elements have been formed inside the stars as a consequence of nuclear reactions or by the actions of the stars (e.g., supernovae). The new elements created by the stars are released into the interstellar medium of the galaxies when they die, and mix with the diffuse gas to form new stars, that now will have a richer chemical composition than the previous generation of stars. Hence, tracing the amount of metals (usually oxygen) within galaxies indicate how much the gas has been re-processed into stars.

Metallicity map of the NGC 1512 and NGC 1510 system, as given by the amount of oxygen in the star-forming regions (oxygen abundance, O/H). The colours indicate how much oxygen (blue: few, green: intermediate, red: many) each region has. Red diamonds indicate the central, metal rich regions of NGC 1512. Circles trace a long, undisturbed, metal-poor arm. Triangles and squares follow the other spiral arms, which is been broken and disturbed as a consequence of the interaction between NGC 1512 and NGC 1510 (blue star). The blue pentagon within the box in the bottom right corner represents the farthest region of the system, located at 250 000 light years from the centre.

Credit: Ángel R. López-Sánchez (AAO/MQ), Tobias Westmeier (ICRAR), César Esteban (IAC) & Baerbel Koribalski (CSIRO).

The “chemical composition map” or “metallicity map” of the system reveals that indeed the centre of NGC 1512 has a lot of metals (red diamonds in the figure), in a proportion similar to those found around the centre of our Milky Way galaxy. However the external areas show two different behaviours: regions located along one spiral arm (left in the map) have low amount of metals (blue circles), while regions located in other spiral arm (right) have a chemical composition which is intermediate between those found in the centre and in the other arm (green squares and green triangles). Furthermore, all regions along the extended “blue arm” show very similar metallicities, while the “green arm” also has some regions with low (blue) and high (orange and red) metallicities. The reason of this behaviour is that the gas along the “green arm” has been very recently enriched by star-formation activity, which was triggered by the interaction with the Blue Compact Dwarf galaxy NGC 1510 (blue star in the map).

When combining the available ultraviolet and radio data with the new AAT optical data it is possible to estimate the amount of chemical enrichment that the system has experienced. This analysis allows to conclude that the diffuse gas located in the external regions of NGC 1512 was already chemically rich before the interaction with NGC 1510 started about 400 million years ago. That is, the diffuse gas that NGC 1512 possesses in its outer regions is not pristine (formed in the Big Bang) but it has been already processed by previous generations of stars. The data suggest that the metals within the diffuse gas are not coming from the inner regions of the galaxy but very probably they have been accreted during the life of the galaxy either by absorbing low-mass, gas-rich galaxies or by accreting diffuse intergalactic gas that was previously enriched by metals lost by other galaxies.

In any case this result constrains our models of galaxy evolution. When used together, the analysis of the diffuse gas (as seen using radio telescopes) and the study of the metal distribution within galaxies (as given by optical telescopes) provide a very powerful tool to disentangle the nature and evolution of the galaxies we now observe in the Local Universe.

More information

– Scientific Paper in MNRAS: “Ionized gas in the XUV disc of the NGC 1512/1510 system”. Á. R. López-Sánchez, T. Westmeier, C. Esteban, and B. S. Koribalski.“Ionized gas in the XUV disc of the NGC1512/1510 system”, 2015, MNRAS, 450, 3381. Published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) through Oxford University Press.

– AAO/CSIRO/ICRAR Press Release (AAO): Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– AAO/CSIRO/ICRAR Press Release (ICRAR): Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) Press Release: Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– Article in Phys.org: Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– Article in EurekAlert!: Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– Article in Press-News.org: Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– Article in Open Science World: Galaxy’s snacking habits revealed

– ATNF Daily Astronomy Picture on 21st May 2015.